‘Good whiskey is like a good song. It requires no explanation. One taste should tell you everything you need to know. No one has to tell you how to feel about it. You simply settle in and enjoy it.’

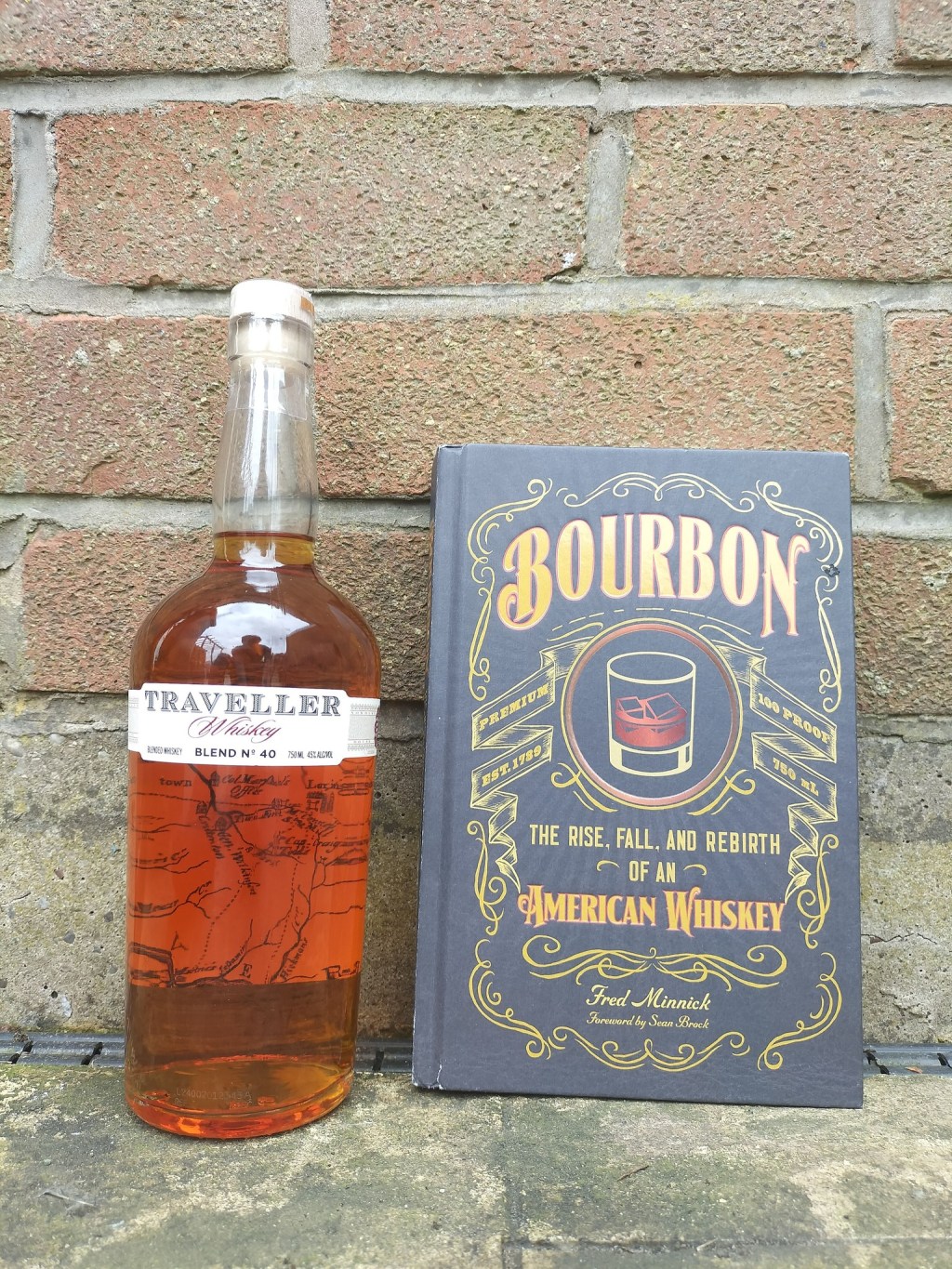

I read this mantra across the bottle of Traveller whisky, turning it around to see every detail. Inside the bottle, illuminated by golden liquid, I see a map marked by Lexington, Kentucky, the beating heart of the bourbon industry. I open the bottle, pour myself a glass and settle into the sound of Tennessee Whisky by 10x Grammy award-winning country singer Chris Stapleton. Traveller is his bourbon.

A drink he created in partnership with the Buffalo Trace Distillery and Master Distiller Harlen Wheatley. It’s a smooth, rambling kind of bourbon. Mild, toasty, easy to drink, exactly the kind of product that goes well with a country ballad. In many ways, the story of bourbon mirrors the most enduring of country songs. Humble beginnings, family values, salt of the earth, small-town living, hard times, good times, rough and ready party times, commercial greed, public controversy, hope, resilience, heart-rending, catchy as hell.

Who Invented Bourbon?

As the spirit of America, bourbon has to have a great origin story. From Henry Ford and the motor car to Thomas Edison and the lightbulb, it’s the American way to celebrate the inventors who changed the world and so too is it with bourbon. A story that existed for many years is that a Virginian pastor by the name of Rev Elijah Craig created bourbon on 30 April 1789 – the day that George Washington became president of the United States. Craig was the owner of Kentucky’s first paper mills and on that day in 1789, a fire broke out behind one of the mills where barrels were being stored.

The fire burned the inside of some of the barrels and workmen went to Craig to ask what they should do with them. A thrifty man, Craig told them to keep the barrels and stick corn whisky in them to see what happened. After some time, it was discovered that the barrels changed the colour and taste of the whisky. If that story sounds too good to be true, then you’re right. It’s pure marketing.

The story of Elijah Craig being the inventor of bourbon was invented in the 1960s when the bourbon industry was fighting to have the whisky be called a home-grown product of the US. Insiders in the industry knew it was false and because there was no internet, it was a lot easier to promote the myth.

The truth is that there are several contenders for the creation of American whisky and to get to the heart of that, we must trace the ingredients back to the source. For bourbon to be considered bourbon, it has to be made with these requirements:

- Made with at least 51% corn in the mash bill and produced in the United States.

- Distilled to a maximum of 80% ABV.

- Aged in charred new oak barrels and barrelled at a maximum of 62.5% ABV.

- No flavourings or colouring can be added.

- The finished product must be bottled at a minimum of 40% ABV and a maximum of 75% ABV.

It’s in the corn that we find bourbon’s origins. When Kentucky became a state in 1792, corn wasn’t the chosen grain for distillation. It was rye. But as more settlers moved west and settled in the Bluegrass State, they planted corn because of its versatility as a crop that could be eaten whole, made into flour and used as animal feed. Between 1813 and 1818, corn started to replace rye as the main whisky-based distillate through the recommendations of influential Northeastern distillers like Harrison Hall, who wrote: ‘I have ever considered the union of rye and corn in mash, as productive of more spirit and of a purer quality, than can be obtained from either grain and if the proportion of one-fourth part of rye can be obtained, it is enough.’

In his later work, Hall also advised against rye mashing and that more experimentation had to be done, though he never advised on corn whisky being stored inside charred barrels. Another name linked to the creation of bourbon is Wattle Boone, employer of Thomas Lincoln, the father of President Abraham Lincoln. This presidential connection adds gravitas to the Boone story. Lincoln’s father worked for Boone, who resuscitated a distillery in Nelson County and he built the first Kentucky distillery in 1780, according to the Lincoln papers in the Library of Congress. But it’s believed that it was actually Boone’s father Walter who set up the distillery and Wattle’s moniker of the father of bourbon was fanned by newspapers that wanted to publish an attention-grabbing story.

This is suggested in an 1897 Louisville Courier-Journal story that read ‘Thomas Lincoln was engaged by Wm. Boone, a distiller … which was then in operation upon nearly the exact spot where the big Atherton distillers now are.’ By 1897, Abraham Lincoln and bourbon’s places in popular culture were already well-established. John Ritchie comes up in bourbon lore too. Born in Scotland in 1752, Ritchie started a distillery in Nelson County and died there in 1792. His activities were recorded in 1895 by one Dr M.F. Coones, who mentioned that Ritchie’s distillery was the source of a famous red liquor in Kentucky. The most likely candidate for the inventor of bourbon is Jacob Spears, whose family settled in Kentucky in the 1780s.

The owner of the Peacock Distillery, Spears is credited with coming up with the name bourbon after Bourbon County. Several records back up this claim and bourbon expert Fred Minnick has laid all of these out in detail in his book Bourbon: The Rise, Fall And Rebirth Of An American Whisky. In 1869, a New Orleans publication The Times-Picayune linked Spears to bourbon’s early days. ‘The first whiskey manufactured in Bourbon county was made by parties who emigrated from Pennsylvania about the year 1790.

The first distillery was erected by Jacob Spears a short time afterwards.’ Minnick also points out that in 1935, Congressman Virgil Chapman spoke of his admiration for Spears as the creator of American whisky: I do not know this as an accurate, historical fact in the year 1790 … a man by the name of Jacob Spears, in Bourbon County, Kentucky, where I reside now, made straight Bourbon whisky, and because it was made in Bourbon County … has been called Bourbon whisky ever since. A Kentucky Democrat, Chapman didn’t have a reputation for hyperbole and wouldn’t have anything personal to gain from mentioning Spears. He was possibly relying on anecdotes and oral history he’d learned from living in Bourbon County.

Distillation Gold Rush, Taxes and Adulteration

Into the 1800s, bourbon production got a major shot to the arm through the efforts of President Thomas Jefferson signing the Louisiana Purchase which involved America taking the Louisiana Territory of 828,000 square miles from the west of the Mississippi River to the Rocky Mountains and into the Gulf of Mexico and Canada from the Spanish and French.

The crown jewel in the Louisiana Territory was New Orleans and the flow of goods into the New World. This meant that bourbon distillers could sell their goods freely through New Orleans in barrels, turning bourbon into one of the city’s most valuable commodities. Jefferson also repealed a whisky tax in 1802, increasing the growth of distillers, wholesalers and rectifiers all looking to cash in on a drink that was displacing rum as the spirit of the nation.

By the 1820s, bourbon had made an enemy of temperance movements that saw it as a demon drink alongside other alcoholic beverages. This image wasn’t helped by the quality of some types of American whisky that were being adulterated by rectifiers with prune juice, tobacco spit and water after distillation. There were no regulations against this at the time and terminology was different. In these wild west days of adulterated whisky, the word straight – i.e. neat – whisky could also mean rectified.

So, rectifiers could market their products as straight bourbon. In this fight for consumer attention, distillers came out with specific brands, such as Oscar Pepper, James E. Pepper, Chicken Cock, Silver Creek and Woodcock. But the most successful brand of the time was Old Crow, named after James C. Crow, who made his bones as a distiller at the Oscar Pepper Distillery, which is now known as Woodford Reserve Distillery. Crow is credited with bringing the sour mash technique to Kentucky, which caught on at other distilleries, killing harmful bacteria in other bourbon mashes.

The whisky that Crow made flew off the shelves and after his death, his name was honoured by W.A. Gaines & Co, who bought leftover stocks and created the Old Crow brand. Meanwhile, the government that had once seemed to work in bourbon’s favour would prove to be capricious. In the Civil War, new whisky taxes were imposed and by 1867, when the whisky tax was $2 per gallon, the whole industry was accused of defrauding the government. Distillers were charged with tax evasion and the strongest of these conspiracies was the plan of the US Treasury Department’s supervisor, John McDonald, who presided over Chicago, St Louis and Milwaukee.

At a trial that indicted many distillers, wholesalers and collectors, deputies would point out that the Great Whisky Ring began with McDonald in 1871. He collected money from distillers and gave it to influential members of the Republican party. The secretary of President Ulysses Grant, Orville Babcock, was named as a co-conspirator. Even more telling is that some of that money was found to have funded Grant’s Republican election campaign and others like it. In the end, Grant pardoned Babcock and McDonald. The trial had sensationalised the conspiracy, leaving a stain on the name of bourbon distillers who’d been fighting to keep their products authentic and free of tax reform. Hope would soon be on the horizon.

Bottled-in-bond Sagas

For a hundred years, bourbon had flowed through America. It had been protected by a passionate and scrappy group of distillers and bastardised by snake oil merchants, unscrupulous wholesalers and dodgy marketers trying to make a quick buck. By the 1880s, the former were sick and tired of having the latter dictate the terms of engagement. But the distillers had their own share of the blame. Many weren’t handling stocks properly and failed to forecast product demand. At the centre of this controversy was bonded whisky.

The kind housed in government-approved warehouses and the government allowed whisky to stay in bond before tax was paid. In 1884, there was an attempt by Congress to pass a bonded whisky act, but it didn’t go through and the response from distillers was to change the bonded age limit to lower their taxation. To some, they came off as bitchy and whiny.

J.M. Atherton of the Atherton Distillery said, ‘whisky dealers all over the country have been making laughing stocks of Kentucky distillers because of the many changes and reforms they favour, but which generally fall through after a great deal of discussion and agitation.’7 But the bourbon producers wouldn’t stop their filibustering.

They argued that bottling spirits in bond would be a lucrative way of selling American whisky exports and that they couldn’t give consumers genuine bourbon if they were at the mercy of the rectifiers and adulteration salesmen. This came to a head in 1896 when Kentucky Congressman Walter Evans passed a bill that allowed the export of bottled goods in a large amount of proof gallons. Distillers were looking forward to greater protection against rectifiers and a step in the right direction of producing pure bourbon.

The Liquors Dealer Association fought back against the Evans bill when it went to the Senate on 16 December 1896 and a hearing was granted. The distillers argued that the wholesalers were against the bottle-in- bond act because they wanted to control the bottling themselves and continue to adulterate to their heart’s content.

The dealers dug their heels in, arguing that the act would only benefit the Kentucky distillers. After a lot of wrestling from both sides, a shaky détente was agreed and on 3 March 1897, the Bottle-In-Bond Act was officially passed. The distillers now had a legally binding guarantee that bourbon had provenance and consumers could legitimately know where a product came from. Reliable wholesalers also had a guarantee that they could continue to bottle whisky out of bond without the need to put government stamps on bottles and cases. This was only a temporary armistice, as the wholesalers were determined to keep on doing what they’d always done, while the distillers wanted to break away completely and bottle their own products.

Skirmishes between both sides continued to happen into the 1900s with further fuel added to the fire after the passing of the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906. Under this legislation, there were no clear legal definitions of bourbon whisky and this lack of definition allowed rectifiers to brand their products as bourbon, even if they were grain vodka blended with rye whisky. As more debates around the Pure Food and Drug Act cropped up, resentment in other states built towards Kentucky, especially Illinois, Indiana and Ohio who accused the Kentucky distillers of wanting to create a monopoly for themselves on what bourbon was allowed to be.

To the Kentucky distillers, they were fighting for their livelihoods. This hundred-year-old struggle of defining American whisky had become tiring for one man – President William Taft. Not long after he took office in 1909, Taft invited everyone with a horse in the bourbon race, along with chemists and those involved in the Pure Food and Drug Act, to reach a consensus on a legal bourbon definition and blends that were deemed as imitation whisky.

The landmark ‘Taft Decision’ decreed: ‘Some time during the Civil War it was discovered that if raw whisky as it came from the still, unrectified and without redistillation, and thus containing from one-half to one- sixth of 1 per cent of fusel oil, was kept in oak barrels, the inside of the staves of which were charred, the tannic acid of the charred oak which found its way from the wood into the distilled spirits would colour the raw white whisky to the conventional colour of American whisky, and after some years would eliminate altogether the raw taste and the bad odour given the liquor by the fusel oil and would leave a smooth, delicate aroma, making the whisky exceedingly palatable without the use of any additional flavouring or colouring. The whisky thus made by one distillation and by ageing in charred oak barrels came to be known as ‘straight’ whisky, and to those who were good judges came to be regarded as the best and purest whisky.’

In other words, the Taft Act as a whole finally etched the words ‘bourbon’ and ‘rye’ next to ‘straight whisky’ in the legal bedrock of the American system and called out the fraudulent rectifiers and blenders who’d been cutting corners for too long. The straight whisky men are relieved from all future attempts to pass off neutral spirits whisky as straight whisky. More than this, if straight whisky or any other kind of whisky is aged in the wood, the fact may be branded on the package, and this claim to public favour may be truthfully put forth.

Taft did more for bourbon than any other president that had come before him, but there was still a long road to travel with many trials and tribulations before America’s spirit could reach the heights that it has today.

Bourbon Barons and Bootleggers

James ‘Jim’ Beam had been carrying the bourbon-making legacy of his family since the age of 16 when he first learned how to make the stuff. In 1894, he officially became the head of the Beam operations, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather, both named David, and his great-grandfather Jacob, who set down the family roots in Kentucky as a humble farmer in the 1780s. The Beam dynasty knew how to make good bourbon and Jim was no exception.

The company’s Old Tub whisky had become a national bourbon brand and was popular, despite the trend of distillers having to shift to industrial alcohol production for the First World War. In 1920, everything came to a grinding halt for Beam with the introduction of Prohibition. Forced to shut down, Beam sold all his booze holdings and moved to Florida. As is the case with many of the great bourbon barons of the twentieth century, Beam had no problem adapting – for the sake of supporting his family, and to the changing times. He took a crack at coal mining and citrus farming, though he didn’t turn out to be much good at either. Beam wasn’t an outlier in turning his hand to something else or getting creative in a climate of all alcohol being banned in the States.

There were always loopholes to find and whisky returned to one of its original guises as a medical product. In 1920, it was used as a treatment for the Spanish Influenza outbreak that killed millions of people worldwide. One pharmacist, F.J. Quirin reported: during the influenza epidemic … whiskey was very freely prescribed by physicians for their patients and as a druggist, I have no hesitancy in saying that … it was the cause of saving many lives … Much more might be said against Prohibition of the kind proposed, but I believe the influenza epidemic alone is sufficient to convince most people of medicinal value in certain areas.

Naturally, some took advantage of this medicinal clause, such as John and Mary Dowling, a couple who would fight against bourbon being an exclusively American product for the rest of their time in business. As co-owners of the Waterfill & Frazier Distillery in Kentucky, the Dowlings had plenty of equipment to lug down with them to Juarez, Mexico, where they started the D&W Distillery. While in Mexico, the Dowlings struck up a connection with the Beam family through meeting Jim Beam’s cousin Joe, and Joe’s son Harry. The US government allowed for small batches of medicinal whisky to be made and as it wasn’t illegal to distil alcohol in Mexico, the Dowlings brought ‘Mexican’ bourbon to the world.

Mary was a firebrand bootlegger who never shied away from making money from whisky wherever it was to be found. Before Prohibition, she’d started unloading 22,000 barrels of whisky from the Waterfill and Frazier warehouses near Tyrone, Kentucky, and by 16 January 1920 she had 1,600 barrels left. She decided to keep the rest ‘safe from the heat’ by storing them at her house and selling them by the bottle with her sons John and Emmett. In 1923, the Dowling home was raided by the police and Mary was put on trial with her children.

The final ruling of the trial came in 1926, with the family being hit by fines of $10,000 and Mary’s sons being sent to prison for a year. By this time, the Dowlings had already started constructing the distillation plant in Mexico. The D&W Distillery had a popular following all through Prohibition, yet their Mexican bourbon was looked down on by Kentucky distillers for the lack of authenticity up until the final day of it being made in 1964, when bourbon was officially recognised and protected as a US-made product.

Back in the US, bourbon distillers didn’t just face opposition from the government. They were being shaken down by criminals forming strong bootlegging rings that were producing their own supplies of illegal booze or stealing legitimate stuff. There was one instance in Lebanon, Kentucky, of four masked men taking guards hostage at the Kobert, Mueller and Wathen distilleries. The gang stole ninety-two cases of bourbon. After two years of constant scrutiny from the government and harassment from bootleggers, the leading US whisky distillers decided to fight back by banding together and referring to themselves as the ‘Custodians’ of pure-bonded medicinal whisky.

They protested that Federal Prohibition Commissioner Roy A. Haynes was playing fast and loose with enforcing Prohibition standards, and their livelihoods were being taken away by criminals. While steps were being taken to limit the influence of whisky bootleggers, the Anti-Saloon League, a temperance organisation, claimed that forwarding the medicinal alcohol movement was undermining the reason for the Volstead Act in the first place.

And so raged a back-and-forth over the importance of whisky for medical purposes between dry politicians and those seeking to legitimise the sale of products perceived to help fight illness. The distillers were either passed from pillar to post in terms of who they needed to talk to, or were sometimes ignored altogether. But a major win for the bourbon industry happened in 1930 when influential bootlegger arrest numbers increased and there was talk of repealing Prohibition from the likes of New York governor Franklin Roosevelt and President Herbert Hoover. The voices calling for repeal started as a trickle and gradually turned into a flood as the Great Depression of the 1930s tanked the American economy.

The temperance crusaders had lost their edge and their arguments no longer held weight for a nation that needed to get back on its feet and whose citizens needed work. Alcohol taxes had also taken a massive nosedive since the start of Prohibition, so making alcohol legal meant taxes could be collected again to jumpstart the economy and buy goodwill for politicians. According to the founder of the Anti-Saloon League, Dr Howard Russell, the main reason why Prohibition was repealed was from the decision-making of ‘American multi-millionaires who want liquor to pay their income taxes.’ It’s hard to argue against that point.

For the bourbon industry, it was fantastic news. For the first time in thirteen years, distillers like Jim Beam could start to fill barrels again and good ol’ Jim himself could finally get back to doing what he did best. By 1933, Beam was 70 years old and would have been well within his rights to ride off into the sunset like a gunslinger who’d earned his reputation ten times over. Instead, he returned to Kentucky and rebuilt the distillery in 120 days. In 1934, he incorporated the James B. Beam Distilling Company, which proudly championed bourbon for decades to come, riding out the waves of continued government taxation, the disruptions of a second world war, and the ‘white spirits’ terror of the decades to come.

Another bourbon dynasty would become closely tied to the Beams around the same time. Five brothers, David, Ed, Gary, George and Mose Shapira, had a string of successful general stores, including one in Louisville. Consummate businessmen, the Shapiras recognised that with Prohibition’s repeal, the demand for bourbon could skyrocket and they wanted to cash in. So the Shapiras decided to make a bet, as explained by Bernie Lubbers, brand ambassador of the Heaven Hill distillery founded by the Shapiras.

‘Let’s keep in mind these brothers were young. They were in their late twenties and thirties, but they had an eye for business and for spotting talent. They met the legendary Harry and Joe Beam, two brothers who had gone down to Juarez, Mexico, to distil bourbon with a woman called Mary Dowling back in the Prohibition days.

Together, the Shapiras and Beams invested in the company that would become Heaven Hill. As Mark Shapira, the current owner, has told me it was between $18,000 – $20,000 and that was a lot of money back in 1935. From there, the first Heaven Hill barrel was made on the 200 acres of Bardstown land on December 13th 1935. For the Shapiras, the collaboration with the Beam family was a bet. They saw an opportunity to be at the centre of the bourbon universe in Bardstown. Plenty of people wanted to jump on the bourbon bandwagon. In the 1930s, it was common for bourbon brands to be bought directly from distillers who wanted to get rid of unwanted stocks and put out young bourbon or blends to get in on the action.’

All this sounds encouraging, but new and old threats loomed for bourbon, including the spectre of the Bottle-In-Bond Act that was set to be revisited.

The Fight for Bourbon Protection

A couple of years after Prohibition, Canadian distillers and wholesalers decided it was the right time to reopen the Bottle-In-Bond wound and try to get the legislation changed. The argument was that Canada wanted blended whisky to be allowed as bottled-in-bond, while Americans pushed back to say the Act was never meant for non-American spirits.

Congress wouldn’t budge and introduced a law that foreign distillers who didn’t comply with this jurisdiction would be embargoed. The Canadian government wasn’t pleased with this decision and warned that it could hurt trade between both countries. Yet trade agreements dropped tariffs on Canadian whisky from $5 to $2.50, encouraging Canadian distillers to advertise ‘Canadian bourbon’.

For example, Seagram proudly displayed on a product ‘every penny of tariff saving is passed on to you … Seagram’s V.O. 6-years-old Bottled-in-Bond under Canadian Gov’t Supervision, $2.09 a pint.’13 This must have been insulting to American whisky makers whose forefathers had campaigned so hard to get the Bottled-In-Bond Act approved. The simple sentence ‘stored in bonded warehouses under US government supervision for no less than 4 years’ had become a trusted sigil among American consumers and a brand awareness piece. Bourbon distillers had nothing to protect them against foreign bourbon labelling in 1937. Salvation came the year after when Canadian distillers were encouraged financially to make blended whisky instead of bottled-in-bond.

This led to the realisation from Canadian distillers that it wasn’t worth the hassle of continuing to push the bottled-in-bond point and they gradually moved to exclusively promoting blends. As was the case with the First World War, industrial alcohol became the focus of distillers during the Second. In a storm of strict whisky price enforcement and antitrust allegations towards liquor companies, the ‘Big Four’ bourbon makers emerged: Schenley Distilleries, National Distillers, Hiram Walker and Seagram.

All four megacorps were touted as controlling half of the whisky production in the US, gobbling up smaller bourbon makers and brands through aggressive acquisitions and being regularly indicted and investigated for illegal practices and monopolisation. Two other distillers, Continental Distillers and Brown-Forman, were also grouped into this bourbon illuminati, butting heads with the Department of Justice and the Senate over advertising, pricing and political contributions towards the Democrat and Republican parties.

Those same political contributions aided the Big Four in allegedly getting the DOJ to drop certain cases and any attempt to break them up by the government was unsuccessful. Into the 1950s, flashy and creative advertising was the name of the game for bourbon brands looking to stake their claim to American drinkers. Interestingly, this was a time when bourbon ads were geared only towards men because distillers didn’t see women as a feasible market.

They had no issue with using women in their ads to entice more men to drink, as evident from Jim Beam, Old Crow, Early Times, Yellowstone and others buying ad space in Playboy magazine. Ancient Age ran a campaign with model and actress Sophia Loren so her likeness could appear in stores as a cardboard cutout in 1967. The brand also featured women heavily in their print ads. One version is a pretty woman holding a bottle of Ancient Age while pointing suggestively towards the male consumer who’d probably be looking at it. The copy for the ad reads: ‘If you can find a better bourbon … buy it! Ancient Age Bourbon is full 6 years old. It’s distilled in one place to assure you of exceptional quality in every bottle … every drink! That’s why Ancient Age is America’s Largest Selling 6-Year-Old Kentucky Bourbon!’

Ironically, a woman would be instrumental in creating arguably the most successful new bourbon of the 1950s – Maker’s Mark. Margie Samuels and her husband Bill Samuels Snr started the brand in 1953 after purchasing the Burks Distillery, which had started in 1805 as a gristmill. Margie was the type of forward-thinking woman who could see the distillery being a travel destination and historical landmark, as she spent time collecting as much history about the place from neighbours as possible and maintaining the original equipment and feel of the distillery.

She also came up with the Maker’s Mark name, a disruptive choice that went against the Southern heritage and imagery that had become standard fare with bourbon. Capped off by the iconic red dripping wax seal, Maker’s Mark launched in 1958 at $6 per bottle, the most expensive bourbon on the market at the time, compared to the general $2 price tag for other products. The brand leaned into this expensive imagery, putting out some of the most creative adverts to ever be seen in the bourbon industry, as seen from a 1966 campaign: It tastes expensive … and is. Maker’s Mark is made expensively; by hand; in small amounts and flavoured with homegrown wheat to make it softer. It’s the softest spoken of the bourbons; you can stay with its easy taste … Unless you really care how your whisky tastes, don’t pay the price for bourbon as good as Maker’s Mark.’

The ’60s became the decade of bourbon. The Bourbon Institute had been formed in New York to champion and develop universal standards and an ambitious marketing campaign was launched to make bourbon as glorious as white picket fences, apple pie and baseball in the American consciousness. This was the time when the myth of Elijah Craig creating bourbon was invented. It was a press release picked up by various press outlets and the more the story circulated, the more patriotic and red-blooded American bourbon became.

The Bourbon Institute lobbied for bourbon to be officially named and protected as a US product, a decision that was finally achieved in 1964. This was after several years of back and forth between Congressmen, especially the stubborn holding out of one New York Congressman by the name of John V. Lindsay. He had ties to a Mexican bourbon distillery but no amount of stonewalling could stop the inevitable.

The two hundred years of struggle for recognition by bourbon distillers had finally paid off. But just as there seemed to be sunny skies ahead, a storm of white spirits blocked out the light.

Riding Out the White Spirits Wave

Into the late ’60s and 1970s, vodka captured the imagination of the American consumer.

What’s interesting about the rise of vodka in relation to bourbon is how distillers responded and tried to adapt. For example, Ancient Age took a cue from vodka as a mixer with soft drinks by positioning its products with orange juice. There was also the rise of ‘light whisky’, a movement motivated by the colourless appearance of vodka. Perhaps the most infamous case of a bourbon distiller making light whisky is Brown-Forman. This involved filtering out the colour of an 8-year-old bourbon made in Pennsylvania and bottling it at 80 proof. This ‘Frost 8/80’ was meant to be Brown-Forman’s answer to vodka, a spirit that could be blended into cocktails like martinis and daiquiris.

The only problem was that the product had a taste and smell that was unsuitable for vodka cocktails and it ended up being an epic failure. Brown-Forman had sunk $4 million into advertising and now had to buy back every unsold bottle they could find. Once they’d collected everything, the company destroyed the stocks and from that day the word Frost became a curse, never to be uttered again in the halls of Brown-Forman.16 The single most damaging year in the history of bourbon might well be 1972. This was when the light whisky madness was in full gear and vodka was close to becoming the top-selling American spirit. The Bourbon Institute was on its last legs in terms of being the leading bourbon education hub in the world.

A year later it would fold into the Distilled Spirits Industry Council with other national spirit lobbies. But as a last hurrah, it published an ad about the ten- year reign of bourbon being the number one best-selling whisky in the world, even if the bourbon industry looked like a sinking ship at the time. But bourbon was still selling and some of the old guard dug their heels in.

Chief among them was Jim Beam, who backed away from the light whisky trend and championed American heritage. Meanwhile, Tennessee whisky brand Jack Daniel’s branched out from its humble country roots and flooded into pop culture on the back of the punk movement in New York and the hair- and glam-metal bands on the Sunset Strip in California in the 1980s. Maker’s Mark also seized its opportunity as arguably the sexiest bourbon in the 1980s, going head-to-head with Jack Daniel’s in advertising warfare.

The rivalry between the two brands was built on potshots and one-upmanship, and Maker’s Mark had some creative bullets with which to load up its gun. Bill Samuels Jr, a savvy marketer who’d picked up his skills from his father, signed an editorial letter that claimed he’d received a phone call from the wife of Jack Daniel, and that her husband’s favourite whisky to drink was Maker’s Mark. ‘She told me that for years, and for obvious reasons, the only whisky her husband, Jack Daniel would drink was the one with his name … Now, according to Mrs Daniel, Maker’s Mark is the only whisky Jack Daniel drinks.’ Brown-Forman owned the Jack Daniel’s brand and it’s tempting to think that with such a brazen shot, the conglomerate would retaliate by suing the jumped-up ‘mom- and-pop’ outfit that had the audacity to oppose it.

Apparently, Samuels Jr invited members of the Brown family to a private party. Owsley Brown, the former Vice President of the company, was said to be there and it’s rumoured he told one executive to make a brand that could compete with Maker’s Mark. This would be Woodford Reserve, and stories have varied on whether this was true or not. The Maker’s Mark brand, although positioned as a scrappy underdog, wasn’t the mom-and-pop operation it appeared to be on the surface.

For one thing, the brand was growing at a lightning pace after the Burks distillery was awarded National Historical Landmark status by the US Department of the Interior and Bill Samuels Snr leveraged that fact to stir up a media sensation. Sales shot through the roof and the Samuels had to put out a memo to say they couldn’t meet the current demand. It was only a matter of time before Maker’s Mark became a victim of its own success and the Samuels decided to sell to Canadian company Hiram Walker. Bill Jr tried to buy the brand from his father but couldn’t match the $15 million offer from the Canadian powerhouse, or its distribution networks and manpower. He settled instead for being a member of the Hiram Walker board. A positive outcome of the bourbon brand rivalry is that it elevated the industry, demanding that its stewards and champions fight to preserve it, as had always been the case when outside influences threatened to derail momentum. This carried through in the 1990s, with a renewed interest in bourbon coming from outside of Kentucky in other states and from the rest of the world. In 1999, the Kentucky Distillers’ Association created a brochure for what would become the iconic Kentucky Bourbon Trail. A ‘holy trail’ of distilleries was presented for bourbon pilgrims to slake their thirst and drink from the well of local history. The year after, a press release was sent out along with a passport that could be stamped and this marketing campaign created a whole new subcategory of bourbon tourism.

The success of the Kentucky Bourbon Trail pointed towards a return to glory for the category, though it wouldn’t be until the mid-2000s that it would achieve heights to match those of the 1960s.

The Modern Bourbon Boom

At the turn of the new millennium, a host of bourbon fan clubs and magazines were cropping up in every corner of the internet. Specialist bars like the Bourbons Bistro opened in 2005 in Louisville, enticing consumers from across the globe to fly in and try bottles they’d never heard of. Seeing the growing appetite for Kentuckian culture, the Louisville Convention Visitors Bureau flew reporters in to review the Kentucky Derby and knock back drams in Bourbons Bistro, Brown Hotel Bar, Galt House and dozens of other local bars that were keen to take advantage of the renewed interest in America’s spirit. These flames were fanned even more by the online bourbon community that had grown across social media and bloggers who sang the category’s praises from the UK to Alaska.

A generation of whisky writers rolled up their sleeves, got their boots on the ground and told readers everything they needed to know. Chief among them was Chuck Cowdery, an author who produced a popular book called Bourbon, Straight. According to him, ‘the biggest change in thirty years is that people are actually writing about whisky now. Thirty years ago, there were a couple in the UK but no one here. When I got into the business, whisky was dead. I worked on many distilled products but few whiskies because whiskies were barely ever promoted back then. Even when I started American whisky writing about twenty years ago, I was a lone voice crying in the wilderness.’

Writers like Cowdery were flying out to meet and visit master distillers who’d attained godlike status among bourbon enthusiasts for the way they conducted themselves and pushed the industry forward. The purest representation of this was Booker Noe. Jim Beam distiller, promoter and raconteur extraordinaire, Noe had a magnetic presence built on down-to-earth Kentucky charm and impish wonder that kept him young and energised. The innovator of the small-batch bourbon technique, Noe popularised mixing the contents of a select group of single-barrel bourbons together to create a product with a unique blend of flavours.

He produced his own iconic bottle called Booker’s and promoted the illustrious legacy of his family until his eventual passing in 2004. However, the modern bourbon boom hasn’t been a total love affair. When controversial practices have happened, fans have been quick to call it out and demand answers. For example, between 2008 and 2016 bourbon brands were lowering proofs and dropping age statements so they could keep up with demand.

Age was an obsession for distillers and they chose to free themselves of worrying about it so they could bottle more of a specific brand. A bonus was that it also made stock forecasting easier, but the passionate bourbon fans who’d started this modern movement sometimes felt betrayed when brands changed age statements. In some cases, it’s led to mass boycotting, as was the case with Heaven Hill and its twelve-year-old Elijah Craig.

At first, Heaven Hill moved the age towards the back label of the product and stated openly that it would keep the 12-year label. Bourbon aficionados weren’t convinced. Commercially, Heaven Hill was thinking that it couldn’t price a 12-year-old bourbon at $30 while other brands were priced at $50. While fans were pissed off at first, they eventually got over it, which highlights the passionate nature of bourbon fanbases and tribes. Bernie Lubbers acknowledges the goodwill that Heaven Hill has built up over the decades and revealed what’s on the horizon at the distillery when I interviewed him.

‘We’ve recently relaunched our flagship Heaven Hill Brand, and now that shines alongside our Evan Williams Brand #2 selling Bourbon and Elijah Craig and others. Mostly, Heaven Hill has stayed within Kentucky and a couple of other states and Evan Williams has been the value brand for the company in the past. We’ve spent the last ten to twelve years trying to revamp the name because it’s the name of the facility that we started at. So, we discontinued the value bourbon brand and then relaunched with a 27-year-old Heaven Hill Select too.

Other recent releases are a 20-year-old corn and an everyday 7-year-old bottle in bond. We’ve got a grain-to-glass release, which is grains that have been grown at the distillery in Bardstown. The corn wasn’t grown there, but the wheat is Kentuckian. There are three different recipes of that and it’s a 6-year-old product. Heaven Hill isn’t the first to do it. But the whole Shapira family are excited to bring it out, especially Max, who even at 80, is spry as ever and in the office six times a week.’

Lubbers is one of the most passionate educators in the bourbon industry whose journey has been evolving since day one.

‘I came into the bourbon industry in 2005 and believe it or not there were only ten distilleries in Kentucky at the time, making up 95 per cent of the world’s bourbon. The only ambassadors that were representing the distilleries were the distillers themselves. They were production- and technical-based people who didn’t have the skills to stand in front of a group of strangers and deliver a talk. Coming from the comedy world, that gave me an advantage. My first role in the whisky industry was working at Jim Beam and I’d already been putting those skills to use by running events and promotions at corner bars to have people taste their products. Instead of using a pre-approved slide deck, I decided to write my own bourbon presentation for a representation of Knob Creek’s 9-year-old product. Since I wasn’t a distiller or a member of the Beam family, I decided I was going to talk about the words on the label and no one was doing that back in 2005. That put me on the map and I was hired as one of the first official ambassadors for Knob Creek.

Without my comedy background, I’d probably have been scared shitless to put myself out there like that and do something that no one else was doing. It wasn’t until I got into the industry and started talking about the words on a label that I saw how trends develop and come back around. Early on, I researched how Pappy Van Winkle and his company, Stitzel Weller, had taken out advertisements on how to read a bottle. So, that confirmed to me I was on the right track. Everything comes back around every twenty to thirty years.

The deeper I went into my research, the more I learned about the rich histories behind the people who created bourbon. Whenever I’d pick up a bottle in training or tastings, I’d tell my audience that the person on the label has a story. The story was what got people interested. As a storyteller and comedian, I’ve focused on my strengths. I’m not a distiller or in production. I’m the face of the brand in the marketplace. Because when I first started bourbon training, distillers were telling me about fermentation and temperature settings and I was like ‘Why are you telling me all this technical stuff that I’ll never be able to present?

So, I told them to give me something I can digest. Give me something I can get excited about that’ll make me want to drink the products, so I can get customers excited about doing the same thing.’

Lubbers also told me it’s new blood that’ll make a huge difference in bourbon’s future growth, highlighting Heaven Hill’s current master distiller Conor O’Driscoll as an example.

‘Conor is amazing at what he does and I can say that from having worked at the two biggest bourbon companies in the world. He’s the only guy I know who’s had experience running small, medium and large distilleries. He’s worked pot stills at Woodford and column stills and done everything in between.

One of his biggest strengths is that he’s come in with a younger set of eyes and is moving Heaven Hill forward for new generations and that does make a difference. Because sometimes you just do what your daddy said, right? That’s certainly true with Parker Beam, who was the master distiller emeritus when I first started. He should be on the Mount Rushmore of distillers but he was always focused on distilling exactly like his dad Earl Beam. He was the master distiller after the Second World War before Parker took over in 1960. If Earl told Parker to do it a certain way, it’d be done a certain way.

I remember Parker always using his body to try and figure out what the state of the bourbon would be like. He’d make assumptions based on how the temperature rose and how it made him feel. Now, doing things the traditional way can be good but it also hinders you. Conor is willing to experiment and make the best possible spirit he can make. One more thing about Conor I’ve noticed is he’ll put his foot down and take a stand against the usual way of doing things when a company might be building a new distillery and they pay consultants a bunch of money to tell them what to do. But he’s ballsy enough to say we’re going to do things our own way and stand by the name that’s on our bottles.’

Indeed, the future of bourbon is bright, with new products, trends and personalities propelling the industry forward. For example, bourbon investment has grown in recent years, with consumers investing in bourbon casks in a similar way that Scotch lovers invest in casks.

Jeremy Kasler, the founder of CaskX, is at the centre of this bourbon investment boom. In an interview with Forbes, he said ‘we think bourbon barrels will continue to rise in value. A couple of things are going to drive that. The first thing that will affect prices is the cost of raw materials to make bourbon. Barrel prices have almost doubled in the last three years; corn is more expensive, and shipping is more expensive. The entire infrastructure surrounding whisky is more expensive, so that’s driving the price higher.’

The second thing Kasler pointed out was that the increasing demand for the liquid will also force prices upwards, alongside big spirits conglomerates buying distillers and creating scarcity in the market. Kasler also believes, bourbon represents a good investment because it is a tangible commodity. ‘When you buy whisky in barrels, you own something, and your money isn’t tied up with something that only exists on trading desks. It’s something you can lay your hands on, especially if you visit the distilleries with us on one of our VIP trips. This is becoming increasingly rare from an investment perspective.’

Elsewhere, distilleries are becoming increasingly focused on sustainability. Angel’s Envy started a campaign in 2014 called Toast the Trees, which focuses on championing the planting and conservation of white oak, which has powerful biodiversity qualities. Angel’s Envy works with the Arbor Day Foundation to run this reforestation programme and in 2021, there was enough white oak planted to sequester roughly 55,000 metric tons of carbon.

Others, such as writer Michael Veach, see the bourbon craze levelling off, but he envisions new artisan distillers providing a 360-degree experience of bourbon tourism, small warehouses for storage and high-quality products. Veach argues that artisan distillers, need to make their top priority making good whisky. The distilleries being built with the main goal of making a lot of money by selling out their brand and distillers to the big companies are in trouble … The big companies have plenty of brands already and don’t need to increase their portfolio or production. Next, the artisan distilleries need to make bourbon tourism an important part of their business plan. Tours are an excellent way to get your product in front of consumers.’

And so, we’ve reached the end of our song. The ballad of bourbon has been an epic ride of highs and lows, triumphs and heartbreaks, rebirths and falls. Every year, new lyrics are added to its story and drinkers will continue to listen along and dance to the music. Long may that song keep playing.

Buy A History Of Alcoholic Spirits: How Our Favourite Tipples Changed The World

This was an exclusive extract from my book A History Of Alcoholic Spirits: How Our Favourite Tipples Changed The World. The book deep dives into the world’s most known and unknown spirits from vodka and bourbon to baijiu and shochu.

It’s an ideal book for casual drinkers, fans of Americana and bartenders who want to improve their category knowledge.

Leave a comment